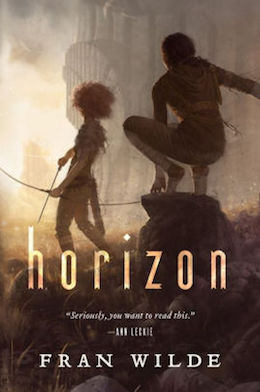

The things I’ve liked best about Fran Wilde’s Bone Universe books—2015’s award-winning Updraft, last year’s Cloudbound, and now the trilogy’s capstone, the compelling Horizon—has been the character of Kirit Densira, accidental hero, accidental city-breaker, and determined friend; the weird, wonderful worldbuilding (invisible sky-squid that eat people! enormous bone towers in which people live far above the clouds! a society based around unpowered human flight!); and the deep concern with consequences.

Horizon is all about consequences.

(Some spoilers for previous books in the series.)

It widens out Wilde’s world to give us a glimpse of further horizons (I’m sorry, I couldn’t resist)—the world of the bone towers must meet the ground, and come to terms with its new dangers and strangenesses and even new people—and new possibilities. Where Updraft was a novel about secrets, bringing hidden injustices into the light, and challenging hierarchies grown stagnant and corrupt because of a monopoly on power and on remembering history, and where Cloudbound was a novel that put the consequences of throwing down the old order at its heart—the political and social conflict when a sudden power vacuum opens up, the destructive effects of factionalism, fear, and scapegoating—Horizon is a novel about apocalypse and renewal, about dealing with utter destruction and a strange new world, and figuring out how to save as many people as you can and build something new.

Kirit, the former Singer Wik, Nat—Kirit’s childhood friend and a former apprentice politician—and former Singer apprentice Ciel have fallen to the ground. They don’t have wings, and below the clouds, on the ground, there are none of the updrafts and wind patterns that let them fly.

They’ve fallen out of the world they knew, where flying was their safety and their way of life, into another one entirely—a world of dust and unknown dangers, where strange beasts lurk on and under the surface. And in their fall, because of it, they’ve discovered a new, long-forgotten truth about the city from which they fell. The city? It’s alive.

But not for long. It’s dying, and in its death, it’ll kill the towers and all their inhabitants. Everyone Kirit, Nat, and the others ever knew or cared about. Unless they can figure out how to bring a warning to the tower citizens above, and figure out how to make sure their warning is believe, everyone will die.

In the city’s heights, tower councillor Macal—Wik’s elder brother—strives to hold his tower together, while faced with an increasing shortage of both trust and resources. The tower citizens he’s responsible for are threatened by two separate factions of violence-prone “blackwings,” as well as from within by fear. And the city is crumbling. When disaster strikes, Macal tries to achieve consensus and figure out what’s physically wrong with the city. But he doesn’t realise that all his efforts are doomed unless he can physically evacuate all the tower residents below the clouds—and he doesn’t even know that a world below the clouds exists.

It’s Nat’s job to tell him. Nat and Ciel, who’ve climbed back up, bringing the terrible news of the city’s fate—and the extremely short timetable for an evacuation that might let people survive. Nat’s less concerned with the city than with his family: his mother Elna, his partners Beliak and Ceetcee and their infant child. As long as they’re safe, Nat’s willing to sacrifice almost anything. He’s prepared to lie and deceive and make pretty much any bargain with his own life, as long as it gets his family the best chance of survival.

Kirit and Wik, meanwhile, have set out to find a safe place for the city’s inhabitants to evacuate to. The ground is a sunless desert, the sky obscured by a haze. And other people live there, people that have different ways and goals, and with whom neither Kirit nor Wik can communicate. They need to find a way forward, to build a future on hope and trust and collaboration, rather than lies—but that’s going to be difficult, because the power-hungry magister Dix has reached the ground ahead of them, and may have already poisoned the well for future co-operation rather than conflict.

As Nat and Macal deal with factions in the clouds and the tensions of evacuating a whole society, and Kirit and Wik try to navigate through the minefield of new and strange perils on the ground—and navigate first contact with a completely different culture, too—they must come to terms with the destruction of their old world. Horizon makes social collapse literal, bringing Kirit and Nat’s city crashing down in totalising destruction. But out of that destruction, Horizon finds hope and co-operation, friction and strife but also community. Horizon doesn’t so much turn from destruction to renewal as it sees destruction and renewal as things that go hand in hand. Ultimately, Horizon is a hopeful book, one about growth and truth, family and reconciliation, and building something new.

I think it could use just a smidgeon more humour—its tone is pretty relentlessly serious—and slightly tighter pacing. But in Horizon, Wilde gives us a compellingly strange world, one that is alien in the best and most interesting senses. And the characters are fun. It’s a worthy conclusion to the trilogy, and a satisfying one.

Horizon is available from Tor Books.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.